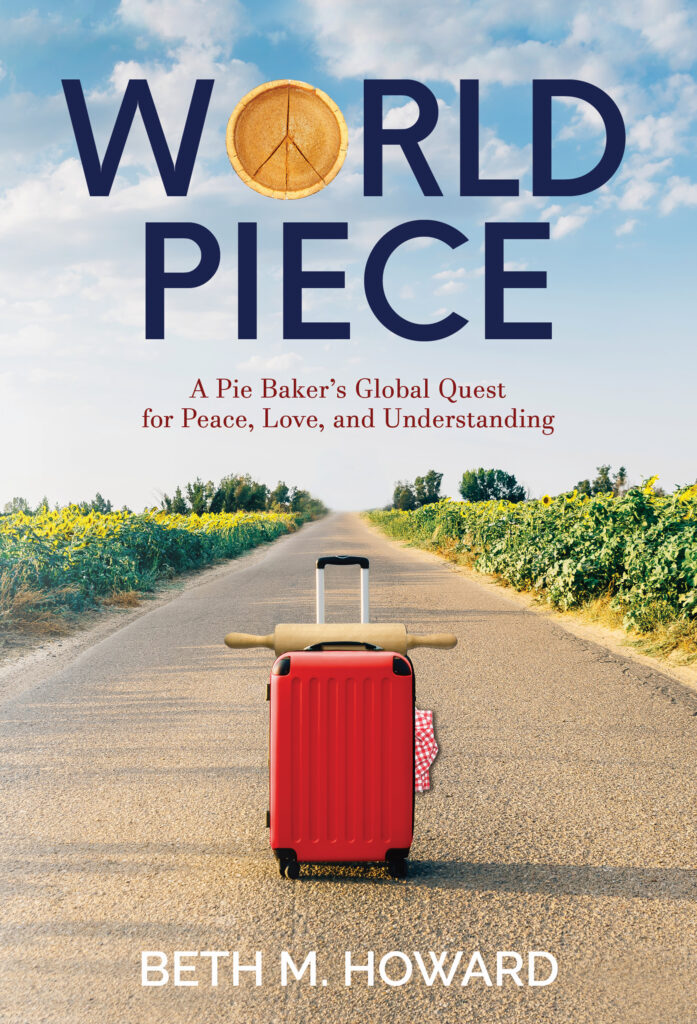

World Piece

BUY NOW from Amazon, Barnes & Noble, or from your local bookstore.

Below, you can read the introduction from my new memoir. You can also watch my humble, homemade film about my round-the-world pie-baking journey. This movie is like pie; it’s not about perfection, it’s about the love that goes into it.

What people are saying about the book

“Part travelogue, part culinary adventure, part love story—and wholly delightful. You don’t need to be a baker, or even a pie lover, to enjoy this delicious book. Read it slowly, though, savoring the humanity found on each page.” — Eric Weiner, NYT bestselling author of The Socrates Express and The Geography of Bliss

“A delicious tale wrapped in a thrilling storyline. There is love, humor, drama, fear, and more humor. From Mumbai’s Dhobi Ghat to the most nuanced pie-making instructions ever written, you will be carried along on this bumpy, swerving, exhilarating ride by a wonderful wit and an infectious enthusiasm for pie and life.” — Bill Yosses, host of Baker’s Dozen on HULU, former White House pastry chef

“I’ve read a great many wonderful travel books over the years (I’m looking at you Paul Theroux and Elizabeth Gilbert), and Beth’s World Piece is among their ranks.” — Robert Leonard, columnist, Deep Midwest: Politics & Culture

“In this brilliant, witty, and wild ride of a story, Howard bakes her way around the world, connecting with humanity to spread goodwill. In short, it’s The Kindness Diaries with pie.“ — Leon Logothetis, TV host, producer, and bestselling author of The Kindness Diaries

“Beth Howard’s delicious sense of humor, self-awareness, and sensitivity brings alive her personal journey, as it intersects with critical issues facing our planet today. Beth reminds us how world peace starts with small acts of kindness—like offering someone a slice of pie.” — Kathy Eldon, filmmaker and founder of Creative Visions Foundation

“Part call-to-action, part memoir, all heart, Howard takes us with her on a whirlwind journey to some of the most challenging spots on the planet. With a raw authenticity similar to Anne Lamott, Howard’s zest for life sings on every page.” — Libby Gill, author of You Unstuck and The Hope-Driven Leader

Synopsis

Beth Howard always dreamed of circumnavigating the planet; not to tick off a list of tourist sites, but to immerse herself in the culture of each country by making pie with local residents. Pie had healed her grief after her husband’s death, so why not use it to heal the world and promote peace? Hauling her rolling pin from New Zealand to Australia, Thailand to India, Lebanon to Greece, Switzerland to Germany and Hungary, Howard uses America’s iconic comfort food as a means for connecting with people in their homes, kitchens, and cafés. In each region, she offers pie lessons and, in turn, learns about the surprising origins of ingredients and traditional dishes—including pie in its myriad forms. During her demanding 30,000-mile, three-month journey, she meets charming characters, experiences uncanny coincidences, and finds kindness when she least expects it. She also encounters geopolitical unrest (past and present) that prompts the questions: Why is world peace so elusive? And what can we do to achieve it? She offers some answers in her feisty, often funny, always unflinching voice. Underlying her pie and peace mission is her personal story about overcoming fear, letting go of grief, searching for a new home, and making room for new love. In what could be described as Waitress meets Anthony Bourdain: Parts Unknown, Howard offers a blend of multi-cultural insight, world history, baking instruction, social commentary, armchair travel, and the comfort of pie, taking the reader on a deeply intimate, delicious, and inspirational global adventure. World Piece is a story for our times.

INTRODUCTION - How to Make an Apple Pie and Change the World

In the Before Times when it was safe to travel—when it was safe to breathe—I packed up my rolling pin, a paring knife, two plastic mixing bowls, and the bare minimum of clothes for both summer and winter climates, and set off on a three-month, round-the-world journey in an altruistic though possibly misguided effort to make pie in nine countries. Pie, I believed, could be a Trojan Horse for peace.

I had wanted to circumnavigate the globe since childhood. I don’t know why. Where do anyone’s dreams and desires come from? A mosquito of an idea enters your being, propagates in your cells, buzzes around in your brain with willful distraction, and no matter how much you try to swat it away it won’t leave you alone until you take action—satisfy the itch, so to speak. Flying around the world in one go, hopping from one continent to the next, decorating my passport with a jumble of exotic stamps, living the pages of National Geographic instead of just looking at them, was something that had always intrigued me—before I worried about things like melting ice caps and carbon footprints. A few fellow travelers I met had done it. Books had been written about it, including one by an environmental journalist friend who, after a divorce, took his kids out of school to visit the earth’s most endangered habitats; another by a guy declaring himself a grump searching for bliss. And, of course, there’s the Jules Verne novel, Around the World in Eighty Days.

Verne’s story was inspired by the first circumnavigation travel package for tourists organized by the Thomas Cook company in 1872, but that was more than three hundred years after the first person, Spanish explorer Juan Sebastián Elcano, made the full circle in 1522. Elcano completed the expedition, but it was Ferdinand Magellan who launched it in 1519. Magellan’s motivation was to collect spices—pie spices like cinnamon, clove, nutmeg—and black pepper. In a time before refrigerators, these spices were as valuable as crude oil because they preserved food and masked the taste of spoiled meat.

Magellan’s expedition was the first of many firsts. The first airplane flight around the world was in 1924, by eight U.S. Army pilots, and the first helicopter flight to circumnavigate the globe was flown by Ross Perot Jr. in 1982 at the age of 23. In 2002, Steve Fossett was the first to circle the planet in a hot air balloon, a feat he accomplished in only fifteen days—after six attempts. Others have traveled by bicycle, by sailboat, by rowboat, by foot, and by myriad other means. In 2015, I merely aspired to strap myself into a coach-class seat on a commercial jet with my pie-making tools stowed in the cargo hold.

I wasn’t vying for some unique travel hook or attempting to set an unclaimed record—this wasn’t Around the World in Eighty Pies. I simply didn’t want to travel as a tourist, touching down just to tick off an entry in 1,000 Places to See Before You Die. I wanted a full-on immersion, to go places guidebooks couldn’t take you, to learn about the people in each destination on a more personal level, and to give back in some meaningful way, more than by contributing a few American dollars.

Adding to the inspiration for turning my journey into a pie-making venture was an illustrated children’s book called How to Make an Apple Pie and See the World by Marjorie Priceman. A geography lesson in the guise of a search for pie ingredients, a young girl gathers eggs in France, flour in Italy, milk in England, cinnamon in Sri Lanka, sugar in Jamaica, and apples in Vermont. I had already been to all those places, except for Sri Lanka, but not for pie-related reasons. My search had been for language lessons in France, leather shoes in Italy, afternoon tea in England, things-I-cannot-mention in Jamaica, and a ski weekend in Vermont.

I bought a copy of the kids’ book just for its title, thinking it should be my title. For starters, I was a pie baker, predestined to be one even, as I was born because of pie. It was the banana cream pie my mom made for my dad that prompted him to propose to her; she knew it was his favorite and it worked, consequently embedding the pie gene into my DNA. I didn’t learn how to make pie from my mom, however. She was too busy raising five kids, shuttling us to swimming, piano, ballet, tennis, cello lessons, and other activities. It was at the age of 17, while on a bicycle trip in Washington State, that I got my first pie lesson—when I got caught stealing apples from the tree of an old man who happened to be a retired pastry chef. I honed my skills over the years graduating from a part-time pie-making job at a Malibu café to running my own pie business in Iowa to teaching pie classes whenever I got the chance. It’s also worth noting that, like my mom, I baked pies for prospective husbands. I made so many, many pies when my mom had only needed to make one. Finally, right before I turned 40, I made a lattice-topped apple pie that led to marriage.

Besides being a pie baker, I was also a traveler and had been all over the world, but not around it, and not in one go. One day, I promised myself, I will make it happen. And I will steal that book title the way I stole those apples from that old man’s tree.

A paperback edition of How to Make an Apple Pie and See the World sat on my shelf for a decade, collecting dust on its skinny spine, and all the while it never stopped taunting me, reminding me of my dream. “Come on,” its seductive combination of words called every time I browsed through my library. “Do it,” it urged as my hand brushed past it to pick out some other volume. “Go.”

But I didn’t just want to make pie and see the world; I wanted to make pie and change the world.

My goal didn’t seem far-fetched, because pie had changed me. Pie had saved my life—twice. The process of making pie—from mixing the dough with my bare hands to rolling it flat and smooth, peeling the apples, and crimping the crust—was a moving meditation, a way to engage all of the senses, an activity that grounded me in the present. My first experience with this was when I left a grueling job as a web producer that drained my soul; I walked away from a six-figure salary to work as pie baker for minimum wage. The baking job drained my savings account, but its curative benefits were worth millions. Eight years later, pie brought me back from the brink after my husband died. Grief—complicated grief was the clinical term—had fought like hell to take me down, but pie helped me win the battle. I made pie for friends, for family, for fundraisers, I even handed out free slices of it on the streets of L.A. By taking the focus off myself to bake for others, pie introduced me to people whose grief was greater than mine and the revelation that anyone could be suffering more than me shook me out of my self-pity. Pie was my therapist, my suicide prevention, my survival. I am not exaggerating when I say that butter, flour, sugar, and apples—and the act of doing something nice for others—restored my will to live.

I had already tested pie’s world-changing abilities in several countries. In South Africa, I taught pie making in a township to a hundred kids who lived in houses with no electricity. In Tokyo, I rounded up local ingredients—Fuji apples and rice flour—and baked with a group of Japanese business people who spoke no English. From Germany to Mexico, pie found its way into my travels, giving me an entrée into people’s homes, cafes, kitchens, and conference rooms.

Pie, I had observed again and again, knows no cultural boundaries or language barriers. No matter where I went, no matter the age, nationality, or language spoken, making a homemade pie and then sharing it with others had the same results. The bakers beamed when their finished pies came out of the oven. They smiled for the camera as they posed for pictures with their pies. And they couldn’t wait to take their pies home to share with their friends, families, and coworkers. I had seen the power of what a simple homemade pastry could do. Spending those few hours baking together, putting down phones and rolling up sleeves, setting differences aside and working together with a common purpose, not only creates something delicious, something tangible, it creates community. Internationally speaking, it’s like the Olympic Games without the competition and everyone is on the same team. Pie unites people. Pie makes people happy. Give a man a pie, you feed him for a day, but teach a man to make pie, just think of the possibilities! If everyone, everywhere, were making and sharing pie the world could be—would be—an exponentially happier place.

In my round-the-world trip, I would travel like a missionary, preaching the gospel of pie, spreading the religion of kindness, generosity, and goodwill. By representing America’s wholesome and earnest qualities through comfort food, I also hoped I could help give our eroding reputation abroad a positive boost. But in my role as pie evangelist, I wouldn’t be imposing my cultural biases on anyone. I wouldn’t claim that my pie is the best pie, the only pie, and that no other pie can lead to salvation. Because pie is agnostic, non-partisan, and pie cannot be claimed by any single country or culture.

This may come as a surprise to some, but pie is not American. It’s an immigrant whose origins can be traced to ancient Egypt, all the way back to 6000 B.C., the New Stone Age, and has remained an integral part of human evolution ever since, proliferating in parallel with mankind. In the beginning, pie dough was made of a flour and water paste to preserve and transport meat. It was the Tupperware of its time, a trend the Romans expanded along with their empire.

Over the centuries, millennia really, pie evolved. Rather than being treated like cling wrap, the crust became edible, buttery, and filled with available foodstuffs like berries, nuts, vegetables, and eggs. The first recorded pie recipe was for a honey goat cheese pie, and is said to be written on a stone tablet in Greece. Pie was embraced in France, where they preferred the single-crust tart style, before moving on to England, where apples first found their way into the dish. The English cookbook, A Proper newe Booke of Cokerye, written in 1545, described how to make pie dough by taking “fyne floure and a cursey of fayre water and a dysche of swete butter and a lyttel saffron, and the yolckes of two egges and make it thynne and as tender as ye maye.”

The Pilgrims imported the recipes, along with smallpox, when they came to America in 1620. Pie, given its hearty nourishment, flexibility of ingredients, and ease of transport, endured with the pioneers, fanning out across the country by way of wagon trains, to become the iconic American symbol it is today.

During my three months of travel, I would not only teach pie-making classes, I would explore the pies of other regions. Mexicans have empanadas; Italians, pizza and calzones; British and Australians, pasties; Indians, samosas; Greeks, spanakopita. If you go by the loose definition of pie—anything that consists of a filling encased in a crust, whether baked or fried, open-faced or folded over—every country in the world has some form of it.

I would sample as many as I could, learn how to make them, and listen to people’s stories about baking and about life. Through this exchange of ideas, recipes, and food, we would forge new friendships, bridge cultural divides, and end up with, yes, world peace. I would call my mission “World Piece”—piece as in slice—and appoint myself as a pie ambassador. I was no social justice warrior. I’m not schooled in international affairs or politics or world history. Nor am I a trained pastry chef or culinary professional. I was just a bleeding-heart idealist with a nagging desire to travel with a purpose, and give back to society in whatever small way I could. Making pie to promote peace and kindness would be that purpose. Bringing people together through pie would be that small thing I could contribute.

I kept stumbling upon films that fueled my world-travel fantasy. In The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, Ben Stiller’s character travels his way out of his stale life. The Icelandic soul-awakening skateboarding scene alone makes the movie worth watching. In Hector and the Search for Happiness, a therapist doesn’t understand his patients until he confronts his own self-understanding by venturing to faraway lands and experiencing other cultures. Good-hearted to the point of naivete, Hector inadvertently tries to date a prostitute, counsels a drug lord, and gets thrown into prison along the way. Quirky but inspiring. And in the documentary Maidentrip, a sixteen-year-old Dutch girl sails solo—solo, at sixteen!—around the world. I remembered being brave when I was sixteen, not nearly as brave as that Dutch girl, but I had been fierce, determined, and hungry for adventure, giving little thought to the things that could go wrong, like dying.

In spite of my desire, along with the proof that many others had circled the planet without falling off its flat edge, I had a long list of excuses for why I couldn’t—or wouldn’t—be able to go on this trip.

One, I wasn’t sixteen anymore. I was fifty-two, young and fit enough to get around, but old enough for the hard knocks of life to add up—and for fear to take hold. I had vowed I wouldn’t become one of those people who becomes more fearful as they age, but when your husband dies unexpectedly at the age of forty-three, as mine had six years prior, your worry quotient shoots way up. I had become afraid in ways I never expected from my previously strong self.

Marcus was traveling when he died, when his aorta ruptured without warning. What if someone else I loved died while I was on the other side of the globe? My parents were approaching eighty, and I worried about them. They both had suspicious moles growing on their skin and needed surgery to remove them. What would the doctors find—if and when their insurance finally approved their treatments? I also worried about my little terrier, Jack. Jack was not just my dog; he was Marcus’s and my dog. An athletic and willful Jack Russell-Yorkie mix, we got him as a puppy when we lived in Germany and when I couldn’t get pregnant, our dog became the child we never had. Jack had just turned eleven. What if he died while I was gone? The thought of losing him, and losing the connection to Marcus he represented, kept me from venturing out too far or too often. It was hard enough for me to leave him for a trip to the grocery store, but to travel as far away as I could possibly go without leaving the planet? And for three months? That was an Ice Bucket Challenge to my inner fire.

And what if I made another bad decision? My track record of recent choices was dismal. Eight months earlier I had moved out of my home, the American Gothic House—the little white farmhouse from Grant Wood’s masterpiece painting—in Eldon, Iowa, where I rebuilt my life after Marcus’s death. Still struggling with grief when I moved in, I elevated pie’s healing powers to a whole new level by opening the Pitchfork Pie Stand, a little summer pie stand that grew into a big pie stand. In the off season, I held pie classes. I baked thousands of pies in the kitchen of that sweet old house. Though in the summer, I baked on the back porch, moving the oven outside like they did in the old days so I didn’t melt the paint off the walls—or set off the smoke alarm as there was always something burning on the bottom of the oven. Between the quiet of country living, the charm of the historic house, and the massive amount of baking, I gradually worked my way back to well-being. But my success was also my demise. Some of the local residents were less than enthusiastic about the increased traffic my pie stand brought to the sleepy town. My pies had made countless tourists happy, but if I was out of pie or, god forbid, closed, they were quick to express their disappointment. The demands intensified after my cookbook was published. People could not get enough pie! Even with the extra help I hired and the generosity of volunteers, I could only make so many. I resorted to wearing a T-shirt that said “Make Your Own D*mn Pie,” but that only made customers laugh and ask if they could buy a shirt along with a pie, so I had to make more T-shirts, too. I was so tired. But getting enough sleep was hard as travelers stopped at the tourist attraction in the middle of the night to take photos, pointing their high beams at the gothic window—my bedroom window. And so, one August morning, four years after I moved in, I decided to move out.

I don’t normally regret my decisions. Always look forward, not back, I say. And that every life experience—good or bad—teaches you something in that What does not kill you makes you stronger kind of way. But my decision to move out of the American Gothic House resulted in a trifecta of loss of my home, my business, and my identity. And that was just the beginning of the hot mess I created.

I left Iowa to move back to L.A., which was where I had been headed before taking what became a four-year detour in Iowa. En route to L.A., Jack and my other dog Daisy were attacked by a coyote outside of Dallas. Daisy, a street dog Marcus and I rescued when living in Mexico, was a white Jack Russell-poodle mix who looked like a sheep, had the street smarts of Oliver Twist, and possessed the docile demeanor of Winnie the Pooh. She was killed, and Jack almost died, escaping with puncture wounds encircling his neck like a ruby necklace. He recovered after spending a week, along with half my life savings, at an animal hospital. If I had lost them both, I’m not sure I’d have lived to tell this story.

Upon losing Daisy, my heart, having only just mended after Marcus’s death, shattered all over again. I blamed myself for what happened to her and to Jack—and for every decision that led to it. How could I go around the world when I couldn’t trust myself to make good choices anymore?

Even going back to L.A. had been a misstep. I was born in Iowa, but had spent the majority of my adult life either living in L.A. or using it as my base. I loved L.A. for its contrasts, its cosmopolitan lifestyle and proximity to nature, high-rises and hiking trails, martinis and surfing, platform sandals and flip flops. L.A. also fulfills my requirement to live near an international airport. So when I returned to L.A. after four years of rural living, I was surprised to find that my urban coping skills had been diminished. I could no longer shrug it off when a Prius with “Save the Whales” license plates snagged my spot in the Whole Foods parking lot or when my neighbor prattled on about her Botox injections. I couldn’t live there again, but where would I go? Where was home?

I prided myself on being a free spirit and was normally comfortable with change. I had moved around so much my dad complained about taking up too many pages in his address book, but this new wave of grief had dismantled my confidence. I would be leaving the country without a home to return to. And like Keiko, the orca in Free Willy, after being released back into the wild, I was ill-equipped to handle this new-found freedom. If I wasn’t secure in my own skin, how could I feel safe out in the world?

There were also the obvious concerns that accompany any big trip, compounded by being a woman traveling alone. Would I have enough money? Or energy? Would I be lonely? What if I got sick or my plane crashed, had a car accident, got mugged, or worse? How dangerous would it be? What if I got lost, more lost than I already was? These thoughts had me spinning on the wind like a fluff of dandelion seed.

There were plenty of reasons why I couldn’t take this trip. Hell, just watching CNN would make even the most well-adjusted person want to stay home. But I had one big reason why I could: I had inherited Marcus’s frequent flyer miles. All 420,000 of them. Marcus had racked them up traveling for his work as an automotive executive for Daimler, commuting between Europe, the U.S., and Mexico. For five years, I had been planning to use them for a round-the-world ticket, so I had been saving them. And saving them. But just like life, frequent flyer miles have an expiration date. I had to either use them or lose them.

If I learned one thing from my husband’s death it’s that life is short. You can put things off until later, but there’s no guarantee that later will come. I was sick of hearing myself talk about my dream—as was everyone else I had been telling about it over the years. It was time to make it happen. I was never going to have this kind of opportunity for free airline travel again, so with less than forty-eight hours before the miles expired, I booked my round-the-world itinerary—scheduling the maximum allowed seven stops moving in one direction—all with a one-hour phone call.

But what happens when dreams become reality? Would my greatest fears be realized? Would everyone be okay while I was gone? Would I be okay? Would my efforts to promote peace have any impact? Would my faith in humanity be restored, along with the faith in myself? Would I make it all the way around or give up along the way? And if I had known how it would all go—known about the illness, the missed flights, the monsoon, the meltdowns, the knife fight, the bombing, the pie thrown into the ditch—would I have ever boarded that first plane?

You can never foresee how things are going to go. No amount of planning, preparation, excessive worry, not even a travel insurance policy guarantees a smooth path. There is no shortcut to finding out what the future holds. No matter how desperate you are for a clue, no astrology chart or tarot-card reading can reveal what lies ahead. You can only take a deep breath and—three, two, one, leap!—trust a net will appear out there somewhere.

THANKS FOR READING! If you’d like to receive updates, blog posts, and other news from me, fill out the “SUBSCRIBE FOR UPDATES” box at the bottom of this page. I also like to hear from readers so feel free to email me directly.

Meanwhile, here’s that short film about my global pie-making adventure.