| The Pie Lady goes to bread school. |

On Saturday I took an artisanal bread making class. I have been teaching baking classes for the past 11 years, not the student of them. But I believe in continuing education, in stretching, growing and expanding. I hunger for new information, crave new ideas and skills, and I’m always up for a new challenge.

Bread is that new challenge.

I’ve made bread before, but I could never get it to rise and, after it baked, it bore a texture and weight—and taste—closer to that of a cinder block than a loaf of edible leavened ground wheat. I may not live in the culinary capital of the world—Southeast Iowa fare (like pork tenderloin sandwiches the size of a dinner plate, Jell-o salad topped with mini marshmallows, and white dinner rolls slathered in margarine) is not exactly refined and sophisticated cuisine—but what SE Iowa does have is The Villages Folk School.

|

| The Magic Chef oven, built in 1935, really is magic. |

Villages Folk School, according to its website, specializes in providing learning experiences in traditional arts and skills, while drawing upon the uniqueness of each of the 11 historic Villages of Van Buren County Iowa. Classes are held in peaceful rural settings so students can return to a simpler time and witness the importance of the artisan in village life.

Try finding that in New York or L.A.! Sign me up!

The bread class was held in the village of Bentonsport, the definition of a peaceful and rural setting. In fact, to wind down the road into this sleepy hollow nestled on the banks of the Des Moines River is an exercise in time travel—back to the “simpler time” of the 1800s. The well-preserved village (with a population of 40) consists of the haunted Mason House Inn, a blacksmith and pottery shop called Iron and Lace, a Native American artifact museum (with an impressive arrowhead collection collected and curated by an eccentric resident who travels by bike), a fudge shop, a kayak rental concession, and a campground. Of note is its bridge that spans the river—built in 1883 for wagons to cross (that’s before the invention of cars!) It’s now a footbridge. The nearest stoplight might be at least 30 miles away.

|

| This is what peaceful and rural looks like. |

Bentonsport resident Betty Printy—also a potter, weaver, and gardener—was our bread instructor who hosted the class in her home, an historic two-story brick and beam house built in 1869. Stepping through her doorway was to enter another world, indeed a simpler one—and safer one. Surrounded by Betty’s antiques—from her 1935 Magic Chef white enamel gas range to her ceramic butter churns and rooster figures to her cuckoo clock—and enveloped in the sweet fumes of her scented candles, I wanted to spend more time here than the four hours allotted for the class. I wanted to move in! Except that I knew from having met Betty before that she had bull snakes living in her basement, in her laundry room, just like I did when I lived in the American Gothic House. Uh, no thanks. Been there, done that.

|

| Betty’s house. |

I didn’t bring up the subject of snakes during class. But we did discuss her numerous aquariums that lined her living room walls. The tanks were packed with fish, inhabitants that far outnumbered the people in Bentonsport. The aquariums, she told us, were the winter home to the convict fish, black sharks, eels, and goldfish that spent the rest of the year living in the ponds situated in the village rose garden. She was caretaker to all. She tried to pawn off some of the guppies on us—they were reproducing by the hundreds—but got no takers.

| Mixing ingredients in a variety of vessels. |

Betty is tall and slender with strong cheekbones and waist-length hair twisted up into a knot at the nape of her neck. Dressed in a baggy white blouse and even baggier khakis, her demeanor was as easy and relaxed as her clothes. She greeted us with her warmth and her smile. “Us” was five participants, all women, all eager to learn this new (ancient) skill.

I always talk about how pie originated in Roman times, how the crust was used to preserve and transport meat. But bread has been around even longer than pie—a lot longer, like even before the invention of language or electricity, before civilization. Prehistoric mankind started eating bread 30,000 years ago! (You think it’s hard imagining a 135-year-old iron bridge made for covered wagon river crossings, try wrapping your head around that number!) And now, here we were, in the Dark Year of 2018, the era of divisive politics, tribalism and social media trolls, questionable news sources and reality TV and talk of building 20 billion dollar border walls: five women (of indeterminate and undisclosed political leanings) gathered together to make— and—break bread.

Like I said, I am used to teaching baking classes. But I was a good little student, a well-behaved participant, inquisitive without being too disruptive, curious and interested. I was there to learn.

|

| This razorblade is a lame, to score the top of the bread. |

And I had a lot to learn.

– About the basic ingredients. (flour, water, sourdough starter, salt, yeast, molasses, olive oil, egg, wheat berries)

– About parchment paper and bread whisks and lames and other necessary tools.

– About sourdough starters — and the care and feeding of them. (Still confounding to me!)

– About the various ways and vessels to use for mixing dough. (Kitchen Aid mixers, bread machines, pots, bowls, stirring by hand.)

– About the numerous steps of preparation. (Let’s just say bread seems more complex and temperamental than pie.)

|

| My friend Lisa adds jalapeños & cheese to hers. |

– About the patience required in waiting for the dough to rise—several times. (Patience is not my strong suit.)

– About extra ingredients added to create varieties of breads. (This is where it gets fun—olives, raisins, cinnamon, sundried tomatoes, cheese, garlic, rosemary, the possibilities are endless. Kind of like how you can put “just about anything” in a pie crust, so it goes with bread, though I have yet to test the limitations of this.)

– About scoring the top of the loaf before baking. (Like vent holes in a pie, the gashes relieve the pressure from steam building up as it bakes.)

|

| Shaping the loaf. |

– About Dutch ovens and clay cloches and baking stones and how they create the steam necessary to get a crusty outer edge. (You can drop some big cash on this stuff, or you can just remember that the pioneers—hell, the cavemen—made bread without any accoutrements. Even today, the Tuareg nomads in the Sahara Desert still bake their bread right in the sand.)

– About baking times and using thermometers to test oven temps and doneness. (As I always tell my pie students, “Never trust your oven. You have to stay vigilant during baking process.” Betty told us the same thing.)

|

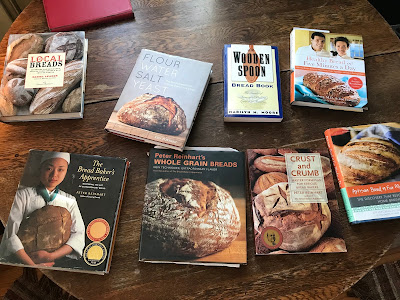

| Homework. Get cozy on the couch and curl up with a good book. |

Like I do for my pie classes, Betty had a long table set up for us to use as a workspace. She had all her equipment and baking tools at the ready. And she walked us through the process, step by step, each of us making our own dough, forming our own loaves, creating our own personal signatures through the addition of extra ingredients and the scoring patterns on top. She had loaves of fresh baked bread for us to sample as we waited for the dough to rise the first time. She had a library of bread cookbooks to look through as we waited for the dough to rise the second time. She served glasses of super-antioxidant berry juice (homemade from her backyard blackberry, raspberry, aronia berry patches) as we waited for the bread to bake.

|

| Snack time! |

Her hospitality made the class so comfortable, but it was her baking methods that especially put me at ease as they echoed my own philosophy. Namely, she didn’t measure precisely.

“Go by feel,” she said as she dug her measuring cup into the flour jar and didn’t level it off or poured molasses out of the bottle letting it flow over the edges of the spoon, or showed us how to feed our sourdough starter adding “some” water as an approximation.

“Your ingredients will vary,” she said, “and sometimes you will need more flour, sometimes less. You have to touch the dough and feel it. If it’s sticky, add more flour.”

Yes! That is how I roll. Maybe I would be able to finally make an edible batard or baguette, ciabatta or pizza crust.

|

| The Victory Shot. |

The four-hour class ended with a victory shot. Instead of taking pictures of my pie students, capturing their beaming smiles of pride as they stood behind their freshly baked beauties, it was me in the shot this time standing behind my spectacular (if I may say so myself) golden brown boule of wheatberry sourdough, smiling with pride. I was even saying the very thing I loved hearing my own students say, the thing that makes the teaching so fulfilling, the thing that must have made Betty feel good about her efforts. I said—we all said, “I can’t believe I made this!”

Steaming and fragrant, the yeasty scent wafted up in my nostrils. I was tormented with desire, desperate to rip off a hunk and shove it right into my salivating mouth. I managed to maintain my manners and waited until I got home to indulge. (Anyway, I had eaten several slices of Betty’s bread during the class so I wasn’t exactly starving.)

|

| Ta da! Mine is the one bottom right. |

|

| Betty checks with her thermometer to see if the bread is done (at 208 degrees.) |

My bread….Oh. My. God. My bread was so fucking excellent, so moist and tender and chewy and perfect I decided to make more the next morning. Betty had given us each our own jar of sourdough starter to take home and I wanted to practice while the steps were still fresh in my head. I wanted the process to take hold, to imprint in my brain and live in my muscle memory the way pie has, to the point where if I lost my vision and my hearing I would still be able to make a damn fine pie. I was determined to achieve the same comfort/skill level with this newfound passion for bread.

I was not so lucky at home, unsupervised without Betty’s gentle guidance and instant answers to my questions, like, “Is it okay to use a packet of yeast that’s six months past its expiration date?” I stepped through each stage—setting and resetting the timer on my iPhone, running downstairs every 30 minutes to “stretch and fold” the dough, transfer the dough to another bowl to rise some more, preheat the oven to 430 degrees, and finally tuck my baby into a cast iron Dutch oven for baking. My dough did not double in size. Was the room too cold? Was it because of the expired yeast? I did not have parchment paper so I used the “other” method of lining my Dutch oven with cornmeal. The oven smoked so much while the bread baked that the smoke alarm went off and sent the dogs into a panic. I had to open the doors to air out the house, and because it was a 25-degree winter day, the smoke was replaced with a stinging icy breeze.

My first solo-run bread, while half the size of the loaf I produced in class, wasn’t a total disaster. It was edible and, given I had stuffed it with cinnamon, raisins and brown sugar, it was still pretty delicious.

I always preach to my pie students, “Pie is not about perfection! It should look homemade!” As I scrutinized my loaf, I had to preach to myself that bread is not about perfection either. This misshapen lump, a little too dark on top, the scoring lines ripped apart like broken skin, was definitely not perfect. But it qualified as looking homemade and I’d take homemade any day.

I am not deterred. I will keep practicing. I will keep experimenting with ingredients, techniques and tools. I will buy some fresh yeast. And I will remember that if the cavemen could make bread, so can I. And who knows, maybe someday I will get good enough at this I will be able to teach bread making. Regardless, I never want to stop learning, stretching and growing, and am already wondering what other classes I can take. Luckily the Villages Folk School has a long list to choose from.