The night before my annual mammogram I was thinking about canceling my appointment. Did I want to be bothered with a trip to the hospital—50 minutes away—to have my boobs squished between two plates and hit with a dose of radiation? No. Did I have any history of breast cancer in my family? No. My mammogram last year was fine. So why go?

|

| The commercials may be more important than you know. |

Just as I was lamenting this to my boyfriend, Doug, who was listening to the Cardinals baseball game on the radio, a PSA came on. “About one in eight women will develop invasive breast cancer over the course of her lifetime,” it began. “If you are 40 or older, get a mammogram every year to avoid cancer—or death.”

Why was this airing during a major league baseball game? It didn’t seem like the right demographic for this. Or…was this message meant just for me? I took it as a sign and went to my appointment the next day.

Two days later I got a call from my doctor. “Your right breast shows no sign of malignancy,” she said, “but…”

But what? I suddenly realized this was not going to be a call to tell me everything looked normal.

“But there is a focal asymmetry on the left. We’ve scheduled an ultrasound for you for at one o’clock tomorrow.”

That they didn’t even ask if the appointment time worked for me made me think they considered my case urgent…as if it were a life—or death—emergency.

After we hung up I sprinted to Dr. Google to figure out what focal asymmetry meant. Did it mean…cancer? I learned that it could—and that was all it took for me to spend the next 24 hours considering the possibility of having The Big C, and all that a diagnosis might imply. A friend of mine had breast cancer and it spread. I went to her funeral a few months ago. (Read the story here.) So to say my imagination went wild would be an understatement.

First, I thought of all the reasons this (cancer) might have happened, and caused my cells to mutate:

Could it be from carrying my cell phone around in the front pocket of my bib overalls—right on top of my left breast?

Could it be from living on the farm, breathing in the pesticides?

Could it be from eating too much meat? (Said farm raises cattle and hogs.)

Could it be from The Great Hormonal Shift known as menopause?

Could it be from the increased stress I’ve had over the last year and a half, the combo of my dad dying (from cancer) and my dog Jack almost dying several times (from diabetes)?

Could it be Karma, that I should have treated people better, done more to help the homeless and the poor?

Next, I thought of all the people (and pets) who would outlive me—the ones I had expected to pass on years ahead of me. I thought of all the crap I would have to get rid of so it wouldn’t be left behind for someone else to deal with. I thought of the old journals I’ve been meaning to burn, the clothes I’ve been meaning to take to Goodwill, the piles on my desk I’ve been meaning to file.

I thought of the things I would do with whatever time I have left:

– Go on more bike rides.

– Eat whatever the hell I want! Especially ice cream.

– Take Doug to Africa on a safari, and to Italy to indulge in the food. (See above: eat whatever the hell I want!)

I thought of all the things I would miss:

– Swimming

– My dog, my goats, my boyfriend, my family

– Cocktail hour on the porch swing

– Feeling the wind in my face

– Peach crumble pie

And all the things I would NOT miss:

– Mean, abusive people

– Guns and violence

– Divisive politics

– Toxic masculinity

– Seeing the demise of our planet

I thought of all the things I’m grateful for:

– Modern medicine and mammograms—and Obamacare

– The love of Doug, my family and friends, all my pets

– The privilege I was born into

– The education I’ve had

– The means to travel the world

– My health (up to now)

I thought of how I would tackle the cancer Angelia Jolie-style—aggressively, by cutting off both breasts. I thought of how I would look with a flat chest and of what I would wear when I no longer needed a bra. I thought of how my hair would grow back, maybe coarse, maybe all gray.

The following day as I drove to the hospital, I saw the familiar scenery in a different way. The sky, the clouds, the blackbirds on the fence posts, the red barns, the white dotted line on the highway, every single detail appeared more vivid, sharper, more meaningful, knowing I might not be on this beautiful earth much longer.

In the Diagnostic Imaging ward, I was ushered to a dark room, disrobed from the waist up, and lay on a bed while a technician moved her wand across my chest. She kept her eyes focused on the black and white monitor—and I kept my eyes focused on her, looking for any trace of concern, any hint of news.

“It’s inconclusive,” she said. “I need to show it to the doctor and see what he says.”

I waited on the table, half naked. To keep myself calm I did some yoga stretches and leg lifts, hoping there was no hidden camera.

When the technician came back, she said, “The doctor wants you to have another mammogram. I’ll walk you over there right now.” She handed me a hospital-issue top. “You don’t need to get dressed. Just put this on.”

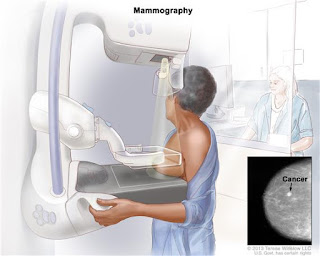

She ushered me into the mammogram room, the same room I had (begrudgingly) been in four days earlier. The technician was, as the others had been, friendly, speaking in gentle tones, and going about her business as usual, tasks that she and her coworkers do daily for hundreds, nay thousands, of other women: Placing sticker with a tiny metal ball on nipples. Positioning body and arms against X-ray machine. Giving instructions to hold breath. Pressing button to take picture.

|

| This is what it’s like, in case you’ve never seen what women go through to get tested. |

She showed me the image, black and white and blurry and, to the untrained eye, hard to comprehend. She pointed out the fibrous tissue, the ducts, the adipose fat, the muscle—the unknown parts of me hidden under the skin.

“This is the area where the doctor saw the spot,” she said. “Where there was a change from last year’s image.”

It was no bigger than a pea. But a pea-size mass is still a mass.

While the doctor was summoned to analyze my mammogram, I sat in the waiting room—in my pink hospital top that didn’t stay closed because of the worn-out Velcro closures. The TV was tuned into a soap opera, “Days of Our Lives,” the one my sister had been on 25 years earlier. The drama was still the same, so were some of the actors, as I recognized a few. As for my sister, she had either been carted off to a mental institution or killed by an ex-lover, or…maybe she died from breast cancer—I don’t remember how her role ended, but seeing the soap made me think back on the last 25 years (actually, all 56 years of my life) and how I had packed a lot of experiences into those years. Maybe I had lived so fiercely because somewhere in my intuition I knew my time would be cut short. Nowadays, it seems like it’s not a matter of if you get cancer (or shot in a school or hit by a distracted driver), but when.

I waited. And waited. It wasn’t long in the scheme of hospital visits, but 20 minutes feels like 20 hours when you are waiting to hear if your life is going to be fine—or if it’s going to hell.

Finally, the technician came back out, took me into the dressing room, and shut the door. Here we go. Here comes the news. I braced myself.

“It’s nothing,” she said. “You have dense tissue so next time get a 3D mammogram. You won’t need to come back for another year.”

When I went outside into the sunlight, I had to blink to fend off the brightness—and the tears. “It’s nothing.” It was not cancer. I was fine.

|

| Let’s do away with these ribbons and find a cure already! |

I was fine, but as I walked out to the parking lot, passing other people walking in, I wondered about all the others who were not fine. The other women whose ultrasounds showed malignant tumors or whose mammograms sent them on to the next stage for a biopsy, and the many (too many) others who were at this moment tethered to chemo drips or confined to hospital beds or taking their last breaths as I walked out with my health—and my freedom.

I sat down by the outdoor fountain at the hospital entrance to collect myself. Relief washed over me like the water cascading down the fountain’s pyramid of gold shingles. And then came the tears, the release of the terror I had been harboring for 24 hours. Soothed by the moving water, I took a few minutes to transition from “this might be the end” to “life goes on.”

In our house we have an expression we have been using since my dog was diagnosed with diabetes last year. “Every day is a bonus,” we say. As we ride the waves of my dog’s good days and bad days, Doug and I remind each other that every day he is still with us is a bonus. As a 56-year-old woman who has had a lifetime of good health, I’ve had no reason for counting each day as a bonus for myself. It even seemed a bit paranoid, fatalistic to count the days that way. But this “little scare” is a reminder of just how quickly things could change.

In a way, I’m glad I went through this as it forced me to consider what’s important to me, and reminded me not to put things off. I now have a list of Things I’d Miss and Things I Want to Do Before I Die that I can consult for those times I relapse into taking life for granted.

|

| Me. Celebrating. Life. |

With my list in mind, I left the hospital and drove—with my windows down—straight to Dairy Queen. I went home and hugged my dog and my goats, went for a swim, and joined my boyfriend for a gin and tonic on the porch swing.

I also put a reminder on my calendar to schedule next year’s mammogram. And guaranteed, when that day comes around, it won’t take a Cardinals baseball game to convince me to keep the appointment. ⧫

Some breast cancer resources:

https://ww5.komen.org

https://www.nationalbreastcancer.org

https://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/mammograms-fact-sheet

Well, what are you waiting for? Go get your mammogram screening. Do it.